Rezension des englischen Klavierauszugs des Oberon, Juni 1826

Review of Weber’s Oberon.

Oberon, or the Elf King’s Oath, a Romantic and Fairy Opera, as performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden; the poetry by J. R. Planche, Esq.; composed and arranged for the Piano-Forte, by Carl Maria von Weber. (Welsh and Hawes, 246, Regent-street.)

The recent and premature death of the composer of this opera, attended by circumstances that tinged with a deeper hue the melancholy feelings which the simple event was in itself calculated to inspire, would have gone far towards divesting criticism of its privilege to censure, had even an occasion been offered. We freely confess our fear that we might have been led involuntarily to discharge in a very imperfect manner the duty imposed on us, had the present work shewn that the mental powers of its composer declined with his bodily strength — that his genius and health had simultaneously received a shock, and decayed together. For, assuredly, we could not have brought ourselves to aggravate the sufferings of a wife and family, to whom was denied the sad consolation of closing a husband’s and a parent’s eyes, by exposing the errors of a last production, or the feebleness of a dying effort. It will however mitigrate the grief of M. von Weber’s relatives, and soften the regret of his friends, to reflect, that the latest of his works will not dim the lustre of his well-earned reputation — that it has already added a laurel to his wreath, and will shortly, when its beauties are by time and acquaintance further developed, exalt his fame far beyond the point it has yet reached, and prove that his imagination was fresh and vigorous while his mortal frame was advancing by hasty strides towards its final dissolution. The music of Oberon consists of twenty-four pieces, including the overture, all of which we shall notice according to their order, and under their respective titles; reserving what we have to add to the general opinion already given, till the conclusion of the article.

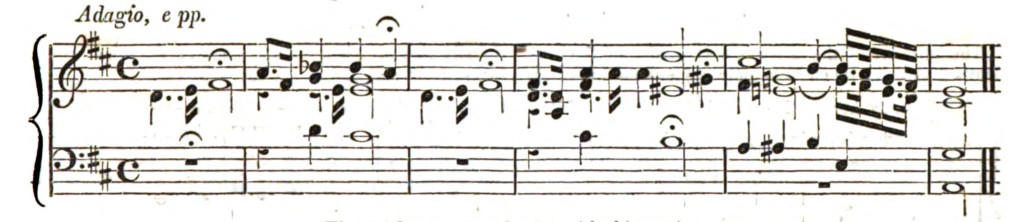

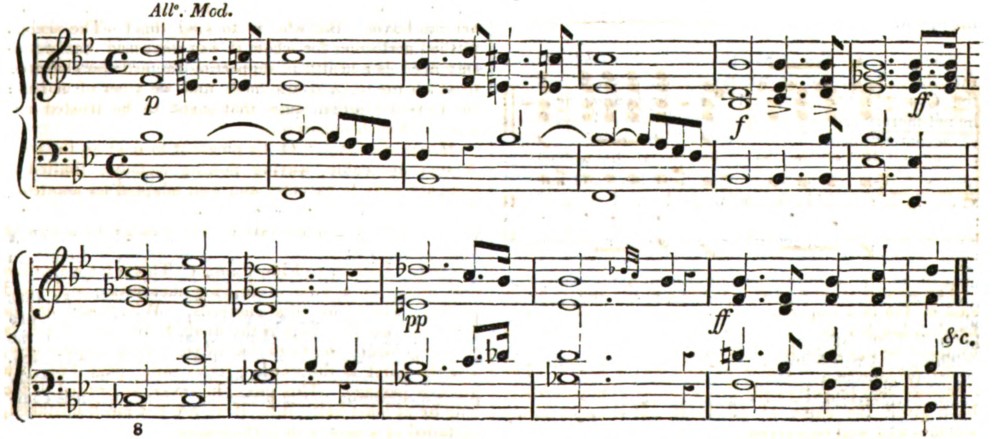

The Overture is highly characteristic of the drama;

there is something exceedingly wild and romantic in its

design, but the principal subjects are never lost sight of,

and are well blended. It opens with a very slow, soft,

and lovely movement, of which the following are the first

bars: —

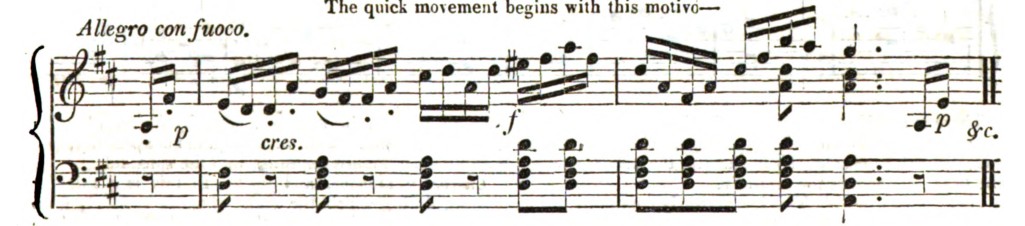

The quick movement begins with this motive —

Part of what may be considered the second subject,

contains the annexed novel and elegant passage, in which

the chord of the seventh appears in a shape that it seldom

takes, though its effect in this form is as good as it is new:

Upon looking closely into this overture, we find more to admire than we at first supposed; it is grand, remarkably ingenious, and its beauties become more evident after a third or fourth hearing.

|The Introduction, “Light as fairy foot can fall,” is a

chorus of fairies, where beauty and science are combined

in so happy a manner, that, to those who judge of it

only from its effect, it seems all simplicity. The few

first vocal bars, and the sylph-like passage of semiquavers

vers for the stringed instruments that follows, will convey

some notion to our readers of the whole: —

A few notes that immediately succeed the foregoing, are peculiarly Weber’s: —

The harmony of the above is well worthy of the

student’s attention; its effect is quite original and beautiful.

Equally charming is a passage, page 14, for two sopranos

and a tenor: —

There is manifestly some error in the fifth bar of the engraved copy of the above passage, which we have endeavoured to correct, by expunging the two c’s from the base, and adding the minim f.

Air, “Fatal vow!” This is a masterly composition, in c minor, nine-eight time. It is full of abstruse harmony, expressive of Oberon’s agitated state of mind, and exhibits some combinations and transitions that the professional musician may study profitably. Unfortunately, it has hitherto been so indifferently sung, as to obtain but little notice.

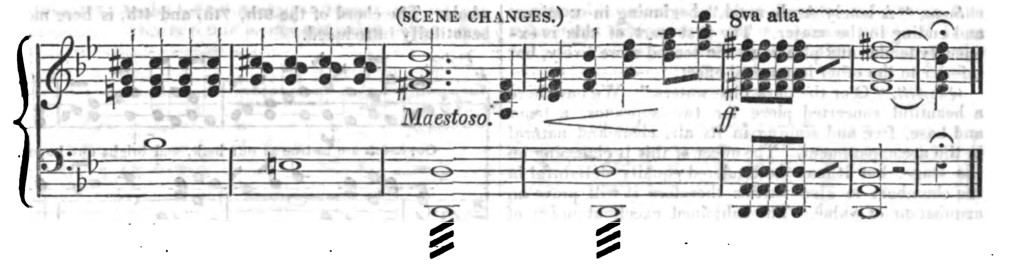

Vision, “O, why art thou sleeping?” — a few pretty

bars ad libitum, in e minor, sung by Reiza, while Sir

Huon is sleeping. This breaks quite unexpectedly, and

with an effect almost thrilling, into the splendid

Chorus, “Honour, and joy.” In this is a solo for

Oberon, during which the scene changes suddenly from

the fairy-king’s bower to the city of Bagdad. The

composer has here produced an effect similar to that by

which Handel, in the oratorio of Samson, and Haydn, in

his Creation, describe the birth of light. The words are,

“But lo! I wave my lily wand,

And Bagdad is before thee.”

The passage is worth extracting —

|

|

Grand Scena, “Yes! even love,” and “O! ’tis a glorious sight.” This is a mixture of recitative and air, a very fine bravura, descriptive of a battle-field, with all its horrors and glories. It is a composition in many movements; some elaborate, others gay and in strong contrast. Among the latter is a enharming allegretto (page 41), “Joy to the high-born dames of France,” and an allegro which is particularly exhilarating and melodious at the words “Fill to the brim,” and “Twine the wreath” (page 43). This brilliant but most difficult scena requires a singer possessing the various powers of the performer to whom it was allotted by the composer; in less able hands it would be lost.

Air (preceded by a short recitative), “Yes — my lord!” in the same grand style as the preceding, is not less difficult to execute, and displays as much talent in the performer for whom M. von Weber composed it. The four bars of introductory symphony, for the violoncellos, are marked by novelty, and the air itself opens in a most magnificent manner. At the repetition of the first words (page 49, last staff), the burst is new and prodigiously grand. In truth, the whole of this, had it been set to Italian words, and brought out at an Italian theatre, would have been pronounced a chef d’œuvre; an observation that will apply with equal force to the greater part of the present opera. This air is the commencement of the finale to the first act, and passes into a duet, in the beginning of which are too many arpeggio passages, fit only for the violin; a fault of which M. von Weber is seldom guilty. The symphony leading to the chorus that succeeds the duet, is one of the many specimens of originality to be found in this work, and shews the vigour of the composer’s inventive faculty. Its effect is uncommonly striking.

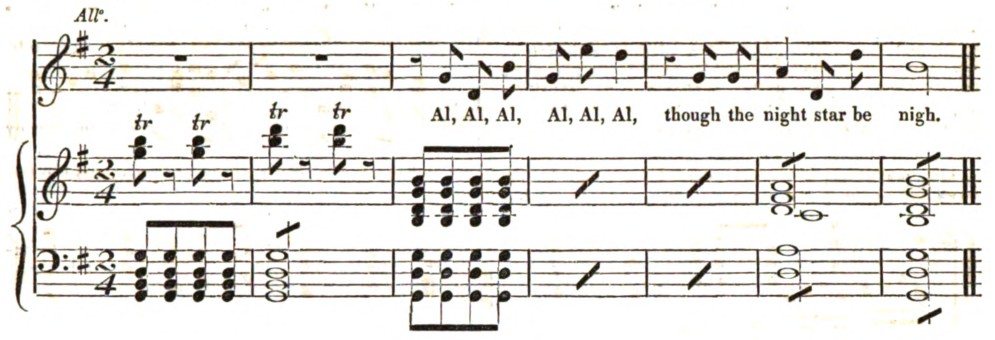

Chorus, “Glory to the Caliph!” — The second act opens

with this curious composition, the whole of which is “rich

and strange,” and makes us wish that we could delude

ourselves into a belief that it represents the music used

at the court of the renowned Haroun Al Raschid; but

the scanty information left us concerning the state of the

harmonic art among the Saracens does not justify an

assumption, that it was more advanced in Arabia than in

Europe at the same period; though we cannot help

thinking that many of the Spanish national airs are of

Moorish origin. That M. von Weber, when composing

this, was influenced by some notion of what might have

been the nature of the music cultivated by that elegant

and learned people, — to whom mankind are so largely

indebted, — we are much inclined to think; and if our

conjecture is correct, an additional proof is thereby afforded

of the spirit in which this great musician imagined

his works. But we must not indulge in the regions of

speculation, therefore we lay before our readers a reality,

in the shape ofa‡ few bars from page 66 of the present piece.

Song, “A lonely Arab maid,” beginning in e minor,

and ending in the major. The first part of this is

extremely tender and pleasing: the second more lively, but

inferior to the other in musical effect.

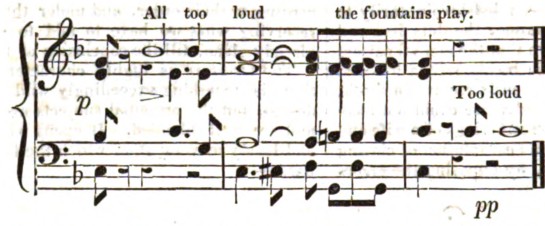

Quartett, “O’er the dark blue waters.” We have here

a beautiful concerted piece for two sopranos, a tenor

and base, free and singing in its air, clear and natural

in the accompaniment. The effect of this is charming on

the stage, but it may be rendered equally delightful in

the chamber; to glee parties therefore it will prove an

acquisition of value. The subjoined excellent union of

melody and harmony (page 80) may give an idea of the

whole. The chord of the 9th, 7th, and 4th, is here most beautifully introduced.

The annexed spirited and admirable passage, to the same words, with a fine running accompaniment in the

base, follows the above: —

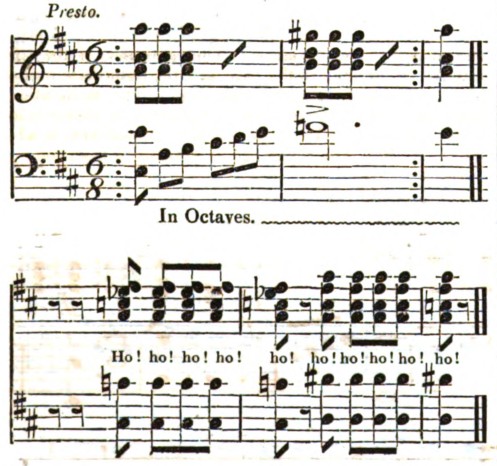

Air and Chorus, “Spirits of air.” This is the incantation

scene, the whole of which is a very deeply-studied,

masterly, effective production. The chorus of spirits is

exactly suited to such creatures of supernatural birth, who

are generally pourtrayed with a strong tinge of the mischievous

in their composition. The following passages

will be immediately recognised as Weber’s: —

The second of these is the laughing of the spirits at the ease of the task imposed on them by Puck; and a very fiendish laugh it is. The music during the storm raised by these beings is highly dramatic.

Air (preghiera), “Ruler of this awful hour.” The composer very properly calls this a prayer: the publishers have given the name of air to it. It is impressively solemn, and well conceived.

Grand Scena, “Ocean!” — The bravura for the principal lady is now introduced, preceded by a fine accompanied recitative, in the following words, which have not been noticed as they deserve: as an act of justice we insert them, and venture to affirm, that had they appeared under the sanction of some commanding name, they would have met with very general praise.

Ocean! thou mighty monster that liest curled,Like a green serpent, round about the world!To musing eye thou art an awful sight,When calmly sleeping in the morning light:But when thou risest in thy wrath, as now,And fling’st thy folds around some fated prowCrushing the strong-ribbed bark as ’twere a reed, —Then, Ocean art thou terrible indeed!There are some extraordinary things in this composition, and many grand effects: the exclamation of joy at the sight of a vessel, is one of the boldest and most successful attempts at expressing passion that the musical art can boast. But who is to sing this? — The accomplished performer for whom it was composed has nearly sacrificed her health in supporting the arduous character to which the scena is assigned, and we know of none on the Covent-Garden stage that ought to be trusted with a piece of such importance.

Mermaid’s Song, “O ’tis pleasant to float on the sea.” A very agreeable, waving, flowing melody; limited in compass, easy to execute, and well adapted for amateurs. The final close is somewhat common, and might be improved by a slight alteration: the change of a note or two would suffice.

Duet, “Hither, ye Elfin throng!” This is for a soprano and tenor, in a kind of dancing measure, simple and pretty. The chorus that succeeds, “Who would stay in her coral cave?” which is the finale to the second act, is very ingenious: the third bar at page 123, is quite new, and the burst at the words “let us sail,” page 125, is a glorious passage. This piece, however, as printed, is too long by at least half: it is, if we are not much mistaken, curtailed of a moiety in performance.

|Song, “O Araby! dear Araby!” — Here the third act

commences. This is full genius and originality, and is

by far the most pleasing air in the whole opera. If so

delicious a song does not become popular, if it is not

found in every house where there is a musical instrument

or a tunable voice, then we shall agree with those who

assert that england is not a musical nation. It is

divided into two movements, the first plaintive, the

second cheerful. — Of the latter some idea may be formed

from the following opening bars: —

The modulation into the minor, at the words “From the drear Anderun,” is unexpected, and eminently beautiful; indeed the whole song shews the creative genious and elegant taste of Weber.

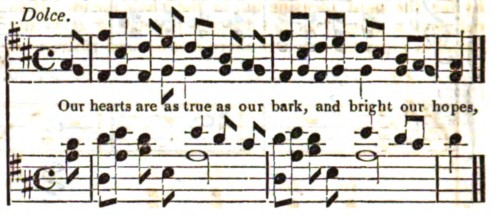

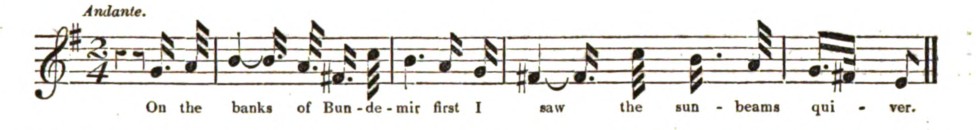

Duet, “On the banks of sweet Garonne.” The commencement

of this is all vivacity, being written for

Sherasmin, the comic character. But when the female,

Fatima, bewailing her captivity, begins the air passes

into e minor, and becomes exquisitively tender, in the

style of the best Irish melodies. We must find room for

a few simple notes from this part: —

The lively movement, in the duet that follows, wherein sentiments inspired by returning hope and brighter prospects are expressed, is not less pleasing, though rather lengthy.

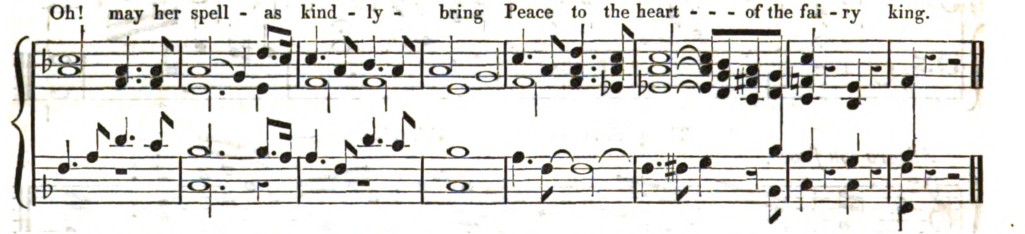

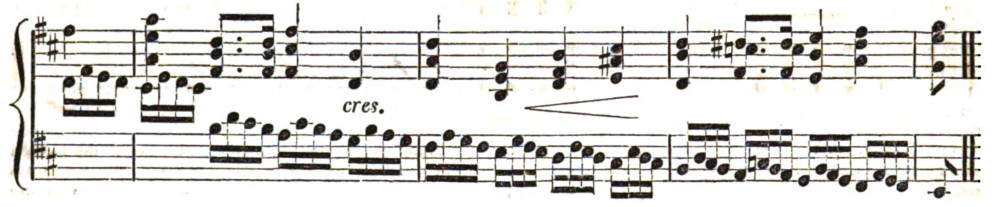

Trio, “And must I then dissemble?” — An expressive

piece for a soprano, contr’alto and tenor, written on the

plan of the terzetto in the Freischütz, and applicable to

the purposes of social music. The conversion of the 4th

into the 7th by a fall in the base, and the immediate union

of the 7th and 4th, are excellent. The modulation

immediately after, from b flat to e flat minor, thence into

g flat, and finally back again to the original key, is

admirable. The whole passage is entitled to insertion.

Cavatina, “Mourn, thou poor Heart.” A beautifully pathetic air in f minor, and not difficult for amateurs. The enharmonic modulation at the words “A cloud may come o’er ye, a wave sweep the deck” is as masterly as impressive.

Rondo, “I revel in hope and joy again.” A brilliant composition, with a good motivo, requiring great flexibility and power of voice, and a distinct articulation. The words in this, as in a former instance, are too many for the notes, and detach the sounds from each other in a manner highly prejudicial to musical effect. But the mode on which the composer has treated the line “Sparkling and leaping in wild delight” is ingenious at least.

Chorus and Scena, “For thee hath beauty deck’d her bow’r.” A scene of dancing and singing united. There is something voluptuous in the whole of this, so far as regards the siren-attempts to vanquish the constancy of the knight, Sir Huon. It must nevertheless be granted, that the orchestra here usurps more of the melody than is reasonable, and reduces the vocal parts to bare accompaniments. The interruptions occasioned in this, by the energetic exclamations of the inflexibly-virtuous paladin, form a well-imagined contrast to the luxurious sounds flowing around him, and the alluring charms by which his faith is tried. In one of the breaks (page 175) is a fine passage, chiefly of semitones, which will not appear new to those who are acquainted with Haydn’s conzonet The Wanderer, and Purcell’s “From thy sleeping mansions rise;” though no plagiarism must be imputed to M. von Weber, for perhaps he was unaequainted with the one, and of the very existence of the other he was, most likely, thoroughly ignorant.

Finale. We now approach the end of this extensive work. The scene opens with a chorus of slaves, in which (page 183) is one of those singular passages that are purely the offspring of M. von Weber’s fertile imagination. Oberon takes his leave of the couple who have by their matchless constancy released him from the intolerable consequences of his inconsiderate oath, and breaks his spell in a few bars of such charming harmony that we cannot help lamenting his final departure. A march, having no very remarkable feature, follows, and a chorus by the whole court of Charlemagne terminates the opera.

The music of Oberon, like that of the Freischutz, shews that the composer of it was well acquainted with what the Count de Lacépède calls the metaphysique de l’art: he not merely created melodies and discovered new forms of accompaniment, but he studied the passions, their shades and effects, and expressed them with a distinctness and force seldom accomplished by means of musical sounds. He was, in fact, a well-educated man, of extensive reading and deep thought, — a man who, had he been spared, would, according to every fair probability, have extended the boundaries of his art; for even in sickness he shewed no symptoms of mental exhaustion, and a very short time before his death he found new musical ideas crowding on him in as quick a succession as when his bodily strength was less impaired.

This opera will be more popular in Germany than in England, and more generally valued here a year or two hence than at the present moment. — M. von Weber outstripped the period in which he lived; he will be better understood hereafter. The power of his genius will be more correctly estimated, when it is considered that he composed the present work while suffering under a mortal disease; that he wrote a portion of it, and altered and finished the remainder in this country, after a long, and to him, fatiguing journey, when our climate had much increased his malady, and while he was labouring under the depressing — and as it proved, well-founded — fear, that he might end his days in a foreign land, without the presence of a relation, or even a near friend, to soften the pangs of the dying hour.

Though M. von Weber had acquired a proficiency in the English language which was quite surprising, the short time that he had devoted to its study being allowed for, yet he had not made himself master of its accents: hence an abundance of errors, arising out of a want of knowledge on this subject, appear in the work now under review. From all blame attaching to these we most completely exonerate the composer, as a foreigner; but censure falls somewhere: it was the duty of the management to provide a qualified person to assist the German musician in a task which, under his circumstances, it was impossible that he should execute in the manner that the public had a right to expect; and if among people of cultivated minds, being lovers of music, an indifference to the present opera should be avowed, we shall not hesitate to impute it to the many instances of false quantity, or accent, and erroneous emphasis, that occur in different parts of the work. It will immediately be granted that these faults are less pardonable when we state that there is scarcely one of them that might not by the exertion of a little thought, and at the expense of as little time, have been corrected, so as to have left the opera, in this particular at least, in a state that might have challenged criticism.

With respect to the mechanical part of the publication, we are not surprised to find several blunders of the engraver: it was necessarily got out in a hurried manner, and could not have benefited much, of at all, by the composer’s revision. The employment of the words “celebrated” — “admired,” and such terms, in the titles of the various pieces, is exceedingly vulgar, and will not sell an additional page: nevertheless these things must, we fear, be endured for awhile.

As some compensation for these complaints, which we could not avoid making, we most willingly acknowledge, that in purchasing the copyright at a high price, in the present difficult and hazardous times, the publishers shewed great liberality, and we hope that they will not have reason to regret their enterprising spirit.

Apparat

Zusammenfassung

Rezension des engl. Klavierauszugs des Oberon

Generalvermerk

Spaltenumbrüche nicht markiert

Entstehung

–

Verantwortlichkeiten

- Übertragung

- Fabian Schmidt

Überlieferung

-

Textzeuge: The Harmonicon, Bd. 4/1, Nr. 42 (Juni 1826), S. 141–146