Besprechung des Klavierauszuges der Oper “Oberon” von Carl Maria von Weber in London 1826

Oberon, or the Elf King’s Oath, a popular Romantic and fairy Opera; the Poetry by J. R. Planché, Esq. composed and arranged with an Accompaniment for the Piano Forte, by Carl Maria Von Weber; parts 1, 2, and 3. London; Welsh and Hawes. Berlin; Schlesinger. Paris; Schlesinger.

Music, properly so called, may now be divided into two species. The most pleasing in its immediate effects, and therefore the most popular is that which is distinguished by melody. This acts directly upon the sense, and as a picture that represents a varied prospect in vivid colours catches and delights the eye of the beholder, in like manner animated traits of melody take the ear and the fancy of the auditor at once, and occasion much of pleasureable excitement from direct and absolute impression. Whether it be expressive of the subject or expressive at all, is neither enquired nor thought of. The ear is gratified, the imagination roused, the spirits are elevated, and all the purposes of listening to music, in the common acceptation of the term, are fulfilled. The early masters of dramatic song, and even those down to a late period, certainly aimed at just expression, but they seldom if ever failed to consider melody as the great light which must illuminate their system. They did not however possess the same extended means of producing new and extraordinary effects that modern science and a modern orchestra afford, though studious of enriching their ground-work of air by all the aids they could derive from harmony. The use which they made of accompaniment shows that their knowledge and their power grew with the growth of instrumental perfection. Still however the composers of this class adhered to the principle of unity as much as possible—they sought the brilliant and the beautiful for present effect—for effect upon the sense, and through the sense upon the fancy, thus creating scarcely more than physical excitement and its usual concomitants. Down to Rossini, the most popular composer of dramatic music that ever existed, the same practice has obtained. These are principally Italians, or followers of the Italian school.

But another race has sprung up which constitutes our second | species. By the phrase we employ it should seem we consider the family to be one of recent date. This however is by no means the case. For perhaps the very oldest writers for the church, those who studied fugue, canon, and contrivance, the writers in forty parts, in short the writers of music for the mind, for study and reflection were the real founders of the school. Leaving this point to the curious, we proceed to the distinctions which especially mark the compositions of the illustrious man whose latest work we are about to examine, who is the greatest and perhaps the most original and peculiar of the German school. Carl Maria Von Weber has indeed instituted a new musical philosophy, for that is the true description—his is the music of thought as well as inspiration—he enquires deeply into the foundation of the human affections—he traces the laws of association, and follows them into practice—he endeavours to discover the relations between the physical and the metaphysical union of art and mind, and to combine all these elements, and work them together, not only into the pleasureable enjoyment of the moment, but to carry them on and perpetuate these emotions by reflection, is the great and permanent distinction to which he aspires. With this view he does not entirely disregard, but he holds the lighter graces of the Italian manner of writing, of that school we have already described, to be comparatively subordinate and superficial. He would be remembered as well as heard, and relished and approved as well as remembered. He employs his strength then upon the grand and solid parts.—Hence the deep consideration, arrangement, and continuity of his designs—hence the unity to be discovered throughout each of his works—hence those traits which are but as links of the chain of thought—hence the masterly combinations that are contrived not only to impress and to express, but which to be understood, demand the whole force of the attention. Neither must it ever be forgotten that the subjects* Weber has been called upon or has chosen to illustrate by | music, are those of an ideal creation—the highest task of that fine phrenzy which

“Exhausted worlds and then imagined new.”

The genius of harmony which awaits his call may be well supposed to rise instant at the summons, and to address him as that fine apparition, the quaint Ariel, addresses the magic-working Prospero—

“All hail, great master! grave Sir, hail! I come

To answer thy best pleasure, be’t to fly,

To swim, to dive into the fire, to ride

On the curl’d clouds;

To thy strong bidding task

Ariel and all his quality.”

The success of Der Freischutz had made its author’s name so popular in England, that nothing could appear to promise greater eclat, than to engage him to compose and to bring him over to conduct the music for one of the great theatres. At this critical juncture, Mr. C. Kemble, one of the proprietors of Covent Garden, had determined upon accompanying Sir George Smart in a tour through Germany—a tour which may well be termed a tour of inspection, because health, relaxation, and pleasure, were not perhaps so much the objects as the view these artists had to better their professional knowledge, by a personal acquaintance with the progress of the drama and of music in that country of philosophers. They therefore made every possible enquiry, and left nothing unsought or unseen that pertained to the subjects of their pursuit. The first public result appears to have been the engagement of Carl Maria Von Weber to support by his presence in England the reputation he had already gained. The piece he was to work upon was drawn from the poetical visions of one of the most inspired of his own countrymen, Wieland—the time, the proudest age of chivalry. Its machinery embraces the spirits of air, earth, fire, and ocean, while the rapid | transference of the hero from clime to clime by this magical agency, affords range and scope for as illimitable flights of the imagination, in adapting the decorative parts (amongst which for a moment we shall include the music) to the illusive and changeful manners of the story. The finest singers the English stage has to boast, upheld the fame of the composer, and every accessory that embellishment could add, was assembled to give him honour due, to stimulate his genius, and dignify the theatre and the occasion. Last not least, Mr. Planché, who has proved the power of his ability in lyric and dramatic adaptation, was employed to fit the poem for the stage. And as he could hardly fail to feel the distinction, so he has expressed his homage to the musician for whom he has written with great modesty and elegance in his preface to the opera.

“The story on which this opera is founded, (says Mr. P.) appeared originally in that famous collection of French romances, “‡La Bibliothèque Bleue,’ under the title of ‘Huon of Bourdeaux.’ Wieland adopted the principal incidents, and weaving them into a web of his own, composed his justly celebrated poem of ‘Oberon,’ which has been tastefully translated into English by Mr. Sotheby. The subject has been frequently dramatized, twice at least in Germany, and twice in England, not counting a masque by Mr. Sotheby himself, which I believe was never acted. At the Baron Von Weber’s desire, the task has been again attempted; and I am indebted principally to Mr. Sotheby’s elegant version for the plot of the piece; but the demerits of the dialogue and lyrical portions must be visited on my head: they are presented to the public but as the fragile threads on which a great composer has ventured to string his valuable pearls; and fully conscious of the influence that thought has had on my exertions, I feel that, even as regards these threads—

If aught like praise to me belong,With him I must divide it;‘I am not the rose,’ says the Persian song,‘But I have dwelt beside it.’”Such is the history of this performance. Two acts, at least, were composed we believe in Germany—it was finished in the house of Sir George Smart, where Mr. Weber has been a guest since the early part of March, when he arrived in England. |

With the avidity of knowledge and the ease of attainment natural to genius, the composer had studied our tongue, and so perfectly does he seem to have mastered the accent, that throughout this entire work we have detected very few and slight inaccuracies. Still however we must consider that a foreign language must detract from the enthusiasm which ought to fire the composer in the moment of inspiration, since many of the finest filaments of association that link thought to thought by their viewless agency, must be lost and broken. Again, although the English are allied to the Germans by a similarity of character, the latter appear to have risen to a degree of intensity in their taste for the romantic and mystical dramas and of science in their musical combinations, which either we have not yet attained or have long since rejected. There are other disadvantages against which he has contended. When the principal parts of the opera were written, he had little other acquaintance with the powers of his singers than the scale of their compass exhibited. Some changes of considerable importance have been even since made, such as the substitution of Madame Vestris for Miss Tree, Mr. Braham for Mr. Sinclair, Miss H. Cawse for Master Longhurst. These however cannot be deemed to be unfavourable, except perhaps that the greater talent of two of the former might have afforded him greater scope and facility. There was no base singer, and thus Weber was deprived of a voice for which he has written very effectively. Now to the story itself. The principal characters are—

Sir Huon, MR. BRAHAM.

Sherasmin, his Squire, MR. FAWCETT.

Almanzor, Emir of Tunis, MR. COOPER.

Oberon, MR. C. BLAND.——Puck, MISS H. CAWSE.

Mermaid, MISS GOWARD. ——Reiza, MISS PATON.

Fatima, MADAME VESTRIS.

Oberon, the Elfin King, having quarrelled with his fairy partner, vows never to be reconciled to her till he shall find two lovers, constant through peril and temptation. To seek such a pair, his “tricksy spirit,” Puck has ranged in vain through the world. Puck, however, hears the sentence passed on Sir Huon, of Bourdeaux, a young Knight, who having been insulted by the son of Charlemagne, kills him in single combat, and is for this condemned by the Monarch to travel to Bagdad, to slay him who sits on the Caliph’s left hand, and to claim his daughter as his bride. Oberon instantly resolves to make this pair the instruments of his reunion with his Queen, and for this purpose he brings up Huon and Sherasmin, asleep before him, enamours the Knight by showing him Reiza, daughter of the Caliph, in a vision, transports him at his waking to Bagdad, and having given him a magic horn, by the blast of which he is always to | summon the assistance of Oberon, and a cup that fills at pleasure, disappears. Here Sir Huon rescues a man from a lion, who proves afterwards to be Prince Babekan, who is betrothed to Reiza. One of the properties of the cup is to detect misconduct. He offers it to Babekan. On raising it to his lips, the wine turns to flame, and thus proves him a villain; he attempts to assassinate Huon, but is put to flight. The Knight then learns from an old woman that the Princess is to be married next day, but that Reiza has been worked on like her lover by a vision, and is resolved to be his alone; she believes that fate will protect her from her nuptials with Babekan, which are to be solemnized on the next day. Huon enters, fights with and vanquishes Babekan, and having spell-bound the rest by the blast of the magic horn, he and Sherasmin carry off Reiza and Fatima. They are soon shipwrecked, Reiza is captured by Pirates in a desert island and brought to Tunis, where she is sold to the Emir, and exposed to every temptation, but remains constant. Sir Huon, by the order of Oberon, is also conveyed thither. He undergoes similar trials from Roshana, the jealous wife of the Emir, but proving invulnerable, she accuses him to her husband, and he is condemned to be burned on the same pile with Reiza; here they are rescued by Sherasmin with the magic horn; Oberon appears with his Queen, whom he has regained by their constancy, and the opera concludes with Charlemagne’s pardon to Huon.

It will be immediately seen and understood, that a composition which aspires to set off and illustrate the train of changeful situation and circumstances appertaining to such a story as this, must be at once mystical and imaginative. It must employ all the resources of art by turns, and still preserve certain traits, that by their re-appearance may serve to keep alive the principal idea (the supernatural agency) in the midst of the distracting diversity. It will also perhaps strike the examiner, that harmony and instrumental combination would be a stronger and more effectual agent than melody, though melody must always be the popular charm of music, and that from the often-repeated character of Weber’s previous productions, such would be the principle upon which he would work. For it cannot have escaped any one who has given the slightest attention to the genius of this composer’s works, that his conceptions are, as we have before described them, at once lofty and full of high phantasy, yet never losing sight of the philosophy of his art or of its deepest science. Hence at once the praise which always follows him, and the censure which sometimes mixes with the commendation.

Weber’s overtures, though they may be thought to be the first in point of estimation, are always the last in their production, for they take their chief characteristics from the opera itself, leading the mind to embrace as it were the general action. This | property it is that makes them so acceptable to the public, not only in their proper place, but as orchestral music. The overture to Der Freischutz,* before we have seen the piece, raises trains of indefinitely wild images and emotions, stimulating the mind to wander in search of the meaning of such “mysterious harpings.” When the opera has been heard, the book lies open—the connection is manifest, and associations are established, as full of fiery shapes as the drama itself. Of such a kind is the one before us.

The overture we have said is so completely framed upon the opera, that perhaps our analysis would be better understood, were we like the author to consider its construction in the last instead of the first place. It is in D major, and opens the main subject of the piece at once by a solo for the horn, which forms the symphony of the vision of Sir Huon, and indeed gives the second title to the piece, being one of the great magical agents. This consists of five bars only, and a few notes lead to a short trait from the chorus of Fairies, taken by flutes, which presents to us these wayward agents of the night. A martial strain from the movement, played in the Court of Charlemagne (the last scene) introduces the hero, and we are to gather his success from the union of this passage with a part of the trio, which is sung before the lovers embark from Ascalon. These, with their transitions and a passage from Reiza’s scena in the second act, carry us on to Puck’s invocation of the spirits. Here we have the preternatural cause of the shipwreck and subsequent distresses of the lovers pourtrayed to us, and these musical themes, variously wrought, form the rest of the overture, which concludes with the melody from Reiza’s scena, and like the story, happily. If we say that this composition does not equal the overture to Der Freischutz, it cannot we presume excite the least surprise, for when has the genius of the musician produced any thing so darkly mysterious, so finely descriptive, so linked together by unity of plan and execution, so rich in its combinations, so powerful in its dominion over the soul? The one before us is certainly original in conception, and it gains on us by repetition, but neither the traits of melody nor the harmonical combinations are sufficiently beautiful | nor frequent to enchain the mind of the hearer like those former works, with which it cannot escape comparison.

The piece itself opens with Oberon’s bower, and here we must so far digress as to inform the reader that all that “can cheat the eye with blear illusion,” has been most tastefully applied. The stage is filled with “the pert fairies and the dapper elves,” who trip in such wild yet soft and measured movement, that never did the moon-beams fall on daintier sprites. We shall quote Mr. Planché’s poetry, to show he has sustained his part.

Light as fairy foot can fall,Pace, ye elves, your master’s hall;All too loud the fountains play,All too loud the zephyrs sigh;Chase the noisy gnat away,Keep the bee from humming by.Stretch’d upon his lilly bed,Oberon in slumber lies;Sleep, at length, her balm hath shedO’er his long-unclosed eyes.O, may her spell as kindly bringPeace to the heart of the fairy king!The music of this chorus is amongst the happiest conceptions (if it be not the most felicitous) in the opera. The voices are all soprani, the parts syllabic and melodious, and the light strains for the dance intervene as symphonies. Nothing certainly can be more elegantly descriptive.

We cannot say as much for the song of Oberon (“Fatal Vow.”) It pourtrays the anguish and dark passions which vex the spirit, but too darkly as it seems to our notion of the subject for such a being. Nor are we struck with the vision. It would be a simple melody, but is quaint, and appears rather the offspring of thought than feeling. The next fairy chorus, “Honour and joy to the true and the brave,” is very effective. It is interspersed by solos for Oberon and Sir Huon, and one “The sun is kissing the purple tide,” for the first has one of those traits of melody which are scattered like flowers on our path here and there. The chorus is at last wrought into an allegro, the fairies singing an incitation to Sir Huon, while the knight has a separate subject (a bravura) running against the syllabic choral part. There are certainly both force and effect throughout. Next follows the aria d’abilità, given to Mr. Braham, which we must | consider to be any thing but worthy either of the composer or the singer. To our ears the introductory and concluding parts were noisy and vulgar, and little besides. The fullness of the accompaniment compelled Mr. B. to desperate vociferation, tore his tone to tatters, and produced no sensation but pity and pain. The andante in the middle, though smooth and better, cannot redeem the movements between which it stands. There are two modes of writing such a song—in pure syllabic declamation or in divisions. Weber adhered to the former, but scarcely with his usual discrimination. The syllabic method may be, and is more true to nature; but it is in such songs that the licence of musical embellishment may be curiously indulged, and especially when the composer has such an agent as Braham.

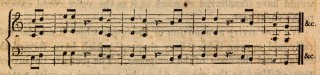

A scena for Miss Paton comes next as if to bring the powers of the hero and heroine into immediate contact and contrast. The lady has however by far the best of the contest, the materials assigned her being much more agreeable, though still not of the highest cast. But we shall cite the principal subject of her song as having a singularity that is worth preserving.

But there is a fault in this song which is common to the author. It is too long—repeats too much, and even when there is diversity, that diversity is not sufficiently varied. This leaves the expression | of sameness and heaviness. We have called this a scena, but the air in truth is only the introduction to the finale of the first act. A dialogue duet succeeds, in which the base, by its mysterious movement, becomes the principal feature, and especially by the transition to G minor near the close, before the parts unite in the allegro vivace. The melody of this has nothing touching, and it lacks the lightness and grace that renders treble duets effective. But in the chorus appended, the genius of Weber is to be recognized. The combinations to the following words are most judicious and striking.

| Fatima. | Hark, lady, hark! On the terrace near,The tread of the haram guard I hear—And lo! thy slaves that hither hie,Show that the hour of rest is nigh. |

| Reiza. | Oh, my wild, exulting soul!How shall I thy joy controul?My kindling eye, my burning cheek,Far, oh! far too plainly speak. |

| Now the evening watch is set,And from ev’ry minaretSoon the Muezzin’s call to prayerWill sweetly float on the quiet air.Here no later must {ye/we} stray,Hence, to rest—Away! Away! |

The charm lies in the continual recurrence of the passage at foot, which appears with uncommon force in the various parts of the accompaniment.

With this passage it is to be observed commences a transition, very finely brought in from the key of E with three flats, to C natural. The soprano at the close has a separate melody, which is principal and brilliant, while the choral parts go on under it. This is one of the very few things that reconcile us to the belief of the possibility of introducing legitimate finales into English operas with success. Most certainly the finale parts of this are | amongst the happiest in the entire piece. The martial but sombre melody of the march is completely characteristic.

The second act calls into more vivid action the preternatural agency which the composer delights to illustrate. This music therefore rises. It opens with a chorus (Glory to the Caliph) which commences in B♮ minor, and changes afterwards very effectively into C major. It is also remarkable for its rhythmical iteration of two quavers and a crotchet, which conveys the accent almost throughout. It reminds us of a part of Preciosa, but is nevertheless very much of the same character as the preceding chorus, to which it bears an analogy, from being sung by the slaves of the Caliph. “A lonely Arab maid,” a song for Fatima, consists of an andante in E minor and a movement in the major, but contains nothing of especial note.

“Over the dark blue waters” is amongst the most attractive pieces in the opera. The opening (Allegro con grazia) consists of two responsive solos in duet, first for the base and tenor, and secondly for the sopranos. Its style accords with the marginal direction, for it is at once free and graceful, with an originality in the structure of the passages, that interests the ear while it engages the attention. When the four parts come in, it rises to the more animated movement which is taken as the principal subject of the overture, and which here in its first and natural position is very exhilarating. In the rolling base passage towards the end (page 83, staff 1), Weber gives a strong proof of his regard to instrumental effects—for it strikes us that many composers would have transferred so much of it as the voice could execute to the vocal part.

We now arrive at a portion of the opera where it may be literally said appear those “fiery shapes,” which have formed the delight and the fame of the composer. The scene is the invocation of Puck to the spirits, whom he summons to raise a storm and sink the vessel in which the lovers are embarked. It begins with a recitative, more powerful than the general tenor of Weber’s writing in this species. Then follows an allegro pesante to the following poetical lines:

Whether ye be in the cavern dark,Lighted alone by the diamond spark,Or beneath the waters deep,Where the prisoned pearl doth sleep, | Or in skies beyond the oneMortal eyes do look upon,Or in the womb of some groaning hill,Where the lava-stream is boiling still—Spirits, wherever ye chance to be,Come hither, come hither, come hither to me;I charge ye by the magic ringOf your faithful friend, the fairy king.The musical effect is drawn from the modulation, which is unusually frequent. But when the spirits answer the call, the stage, nay earth and air seem to be peopled with ideal shapes. The mountain which forms the entire flat (we believe is the theatrical phrase) at the back is divided into countless cells, from which issue all the pigmy inhabitants, while the stage itself is filled with the airy creation of the spirits of other elements. The movement is a rapid presto, but the vocal parts are syllabic. There are one or two striking proofs of the character of deep thought, which is so peculiar to Weber. To the demand

We are here! we are here!Say, what must be done?Must we cleave the moon’s sphere?Must we darken the sun?Must we empty the ocean upon its own shore?Speak! speak! we have pow’r to do this and more!Puck replies—

Nay, nay, your task will be, at most,To wreck a bark upon this coast,Which simple fairy may not do,And therefore have I summon’d you!The spirits answer—

Nought but that? Ho, ho, ho, ho!Lighter labour none we know.Winds and waves obey the spell!Hark! ’tis done! Farewell! farewell!The passage that we would cite is the first line, “Nought but that.” Upon these words Weber has put all the orchestra and the singers into unison, obviously to display the simplicity and easiness of the allotted task—and again in the words,

“Winds and waves obey the spell,”the voices are in unison, and in slow protracted notes, each occupying a bar, to declare the solemnity of the purpose, while the trembling of the instruments convey the first effect as it were of the agency upon the surrounding objects. This is certainly very masterly and very expressive. The storm then rises, and the | orchestra is made the vehicle of the elementary confusion. Like the sea-bird in the tempest, the composer seems to delight in the flash of the lightning, the roar of the thunder, and the heavings of ocean, while he rides in the whirlwind and directs the storm.

The adjuration of Sir Huon is a short and feeling strain, but not in the happiest manner of the author, and is followed by “Ocean thou mighty monster,” a grand scena for Reiza. Considered merely as a descriptive piece, this song is powerful, and perhaps it ought not to be regarded in any other light. The scena represents the gradual calm of the troubled waters, the breaking of the sun through the gloom, and the arrival of a boat to the succour of the distressed Reiza. All these natural circumstances, with the sensations they create in her bosom, form the subject of the scena, and the composer has strictly adhered to the intention of adapting it to the sole purpose of dramatic effect. The recitative is the part which calls for the greatest exertion of vocal talent. It is powerfully conceived. The allegro then presents to the ear (as the scenery to the eye) the distant rolling of the yet angry billows, and the gradual re-appearance of light. In this movement an instance of false accent occurs. In the line, “Through the gloom their white foam flashing,” the emphasis falls on THE and THEIR. At the end of the allegro there is a recitative to describe the busting forth of the sun, and the very fine andante maestoso which succeeds, seems to catch at the instant a portion of the warmth and light of the glaring orb, and to increase in dignity as the object it depicts increases in splendour. It is however curious that Weber should have described the setting sun by a rising passage. The only way in which this treatment can be accounted for is upon the supposition that the composer purposes to convey the flood of glory bursting through the skies, till, as is the natural fact in tropical climtes,

“With disk like battle target, red,He rushes to his burning bed,Dyes the wide wave with bloody light,Then sinks at once, and all is night.”Mr. Planchè may probably have unconsciously had this image of Scott in his mind when he wrote his lines, and the concluding musical phrase seems to give the elucidation we have hazarded. |

An animated movement, at the appearance of the boat, contrasts with the andante, but the last part of this song is decidedly too instrumental; the melody which concludes it is not vocal, and it lies too high, and requires too much effort in order to overcome the force of the accompaniments. The immense effect sought in this scene requires a far more powerful agent than the voice, but every possible assistance from the orchestra is given, and it is in descriptive music that Weber’s forte lies.

The mermaid’s song, “O ’tis pleasant,” is a beautiful and smooth piece of melody, and to poetic dream recalls the memory of the Siren of old—

“Uttering such dulcet and harmonious breath,That the rude sea grew civil at her song.”“Master, say,” a duet between Oberon and Puck, follows, and and‡ is one of the prettiest things in the opera. The opening to the finale of this act, “Who would stay in her coral cave,” describes most effectively the “mustering of spirits.” The chorus itself is beautifully imagined, and the effect is left to the voices, which cannot do justice to its delicacy and grace—however sweet, they can hardly be sweet enough. The scene itself is enchanting. It is moonlight on the sea shore, which is covered by fairies, | whilst the sea itself bears its nymphs, most beautifully grouped, and sailing over its calm surface in their “emerald cars.”

The first piece in the third act, “O Araby, dear Araby,” is a song for Fatima, consisting of two movements, an andante and allegro—the first plaintive as the memory of joys that are past, the second, lively, like the hope that survives even in slavery—for such are the feelings and the situation it is intended to pourtray. We have good reason to believe that this air was a favourite with its author, who was the last man in the world to over-value his own productions; but he esteemed this to have some claim to originality, even at this time of day. If it have such a claim, it lies in the position of the accent in the melody upon the burden, “Al, al, al,” whenever these words occur, as well as in the melody itself. As sung by Madame Vestris, this trifle (for such it must be esteemed when compared with the more lofty and ambitious parts of the opera) is always amongst the most pleasing to the audience. It is loved like a child who engages by its playfulness. We can scarcely decide whether the duet which succeeds was or was not intended to be comic by the poet and the composer—the words certainly indicate such a design, and the music of the first strain given to Sherasmin it allied to the comic species; but when we find in the response of Fatima the major converted into the minor, and a plaintive character substituted both in the melody and accompaniment, a curious difference (we will not call it an anomaly) is presented. Both however agree in determining to be “merry” as “true,” and the duet accordingly closes lightly. This portion is however a little too much drawn out.

“And must I then dissemble” is a trio of great originality, which by the pure force of its simplicity and beauty turns a situation of no importance into one of comparatively deep interest. It is sung by Sir Huon, Fatima, and Sherasmin, on discovering that Reiza is in the power of the Emir of Tunis, to these words:

And must I then dissemble;No other hope I know;But let the tyrant tremble—Unscathed he shall not go.Viewless spirit of power and light,Thou who mak’st virtue and love thy care,Restore to the best and the bravest knightThe fondest and fairest of all the fair;—Spirit adored, strike on our part—Bless the good sword and the faithful heart! |This is made into a beautiful cantabile prayer, with very simple accompaniments, and purely vocal.

“Mourn thou poor heart” is a short but expressive cavatina for Reiza, in F minor. In this there is no execution—there are no difficult or unvocal distances—all is smooth, flowing, and pathetic. The accompaniment is of the same character.

A rondo for Sir Huon, (“I revel in joy and hope again”) is designed to convey the rapture of unbounded satisfaction, but the song is over-wrought, and the passages are consequently stiff and not very graceful. There is a good deal of mannerism, particularly in the accompaniments, and it is too long.

The next is the scene of Sir Huon’s temptation, when amidst the luxurious softness of the haram he is beset by the attendants of Roshana, who dance around and enwreath him with flowers. The strains they sing are voluptuous and bewitching. The solos for the knight, in which he breaks away from their allurements, are powerful and effective, but deformed by the mannerism of a too frequent use of chromatics, and of a tremando accompaniment. The choral parts are however those which absorb the attention.

In the last scene Sir Huon and Reiza are bound to the stake, and are surrounded by black slaves bearing torches, when suddenly Sherasmin blows the magic horn, which sets them all dancing. The chorus sung by the slaves is very ingenious; it is in D major, and begins by a few piano notes from the horn, which gradually swell into a chorus, and one of which the whole melody consists of five notes—but its simplicity bestows its effect, and we must further add, that the analogy before observed in the two chorusses of black slaves in the first and second acts is preserved in the present. It changes at length into a quartet for the four principal characters, on the same subject. Oberon appears, and takes his farewell in a short but characteristic recitative and air, and having transported the principal dramatis personæ to the hall of Charlemagne, he vanishes. This scene is splendid; a spirited march, part of which is in the overture, opens it; one of the best recitatives in the whole piece obtains Charlemagne’s pardon for Sir Huon, and the opera closes by a finale of great brilliancy, the originality of which is derived from the base, which forms the support and ground-work of the whole, and is of a very decided character. |

Such is the imperfect analysis of the last considerable work of Carl Maria Von Weber. We readily admit that it is and must be imperfect, because in the first place it is impracticable fully to comprehend the effects of the score from the study of any arrangement, and next because Weber’s compositions, and this perhaps more than any, are to be judged as musical rather by the instrumental combinations than by any other part, and as philosophical by their position and adaptation to the scene and the passion. In truth, the first time we heard the opera, we abandoned the singers and listened almost entirely to the orchestra, for it could not escape the most casual observer, that it was there he had “placed the statue.” In these combinations there is originality force, and effect. The expressiveness of the whole so much depends upon them, that the opera must be heard to be understood, and as we have before said, must be understood to be relished. But while we give the highest credit to the deep thought which the composer has bestowed upon his work, and the science that reigns throughout, we cannot conceal from ourselves that there is not enough of melody to render it popular, or even greatly pleasing. It is for the few. There is also no small quantity of mannerism. He too frequently forgets, in the search after the philosophical and the sublime, the relative powers of his agents—the voice, which in spite of all the science of the scientifiic, the hearts of a mixed audience pronounce to be the first and chiefest, is too much disregarded and often totally overpowed‡, to make way for the band, the wind instruments especially,* and the noisy over the more harmonious. The compensation must however be sought and will be found by those who love instrumental effects, in the depth, originality, and force of his conceptions in the employment of the orchestra, in the ingenuity, contrivance, and connection throughout—in short, in the invention and adaptation of what we may call the musical machinery of such operas as Der Freischutz and Oberon—the latter being perhaps the most vocal of the two. We nevertheless are compelled to believe that the world will be disappointed—the more so from the previous and possibly exaggerated encomiums on Der Freischutz.

Before we had concluded this article, Death had taken Weber from us. Our opportunities of seeing and conversing with him | had not been many, but they were frequent enough and sufficient to make us acquainted with the purity of his mind, with his quiet, ingenuous, and philosophical temper, with his acute power of perception, his strong but mild and rational judgments, and above all with his intense love of his art, which he prosecuted less for the honour and emolument it brings than for itself. He disdained to lower its noble purposes, and wrote with a view to the fame which is bestowed only after the longest and the closest investigation of the merits of the claimant, not to that which is the hasty tribute of the moment of gratification. Peace be to his ashes!

[Original Footnotes]

- * Those who love metaphysical research may find curious matter in the contemplation of the fact, that some of the most beautiful and most perdurable music amongst the productions of English genius, is written for similar purposes. Dryden’s world of spirits, in his “Tyrannic love,” and Shakspeare’s “Tempest,” gave birth and being to Purcell’s noble compositions—Macbeth was the parent of Matthew Locke’s “wild and airy” music. Single | specimens might be traced out with similar success amongst the works of the composers of all countries and all ages—so intense is the working of the imagination when directed towards the visionary creations that seem to awaken all the powers to their utmost stretch of energy. But at the same time it will be seen by what totally different means these composers and Weber wrought their purposes.

- * See Musical Review, vol. 6, page 388.

- * This is eminently the case in Sir Huon’s song in the first act.

Editorial

Summary

Besprechung des Oberon von Carl Maria von Weber

Creation

–

Responsibilities

- Übertragung

- Jakob, Charlene

Tradition

-

Text Source: The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review, Jg. 8 (1826), pp. 84–101